Microscopy as a Hobby

For many people, observing nature is synonymous with relaxation. It is a step toward a lost paradise, where humans were connected to nature, in a sense alien to culture. Today, humans define themselves virtually by their quality of being living beings in an artificial, culturally and civilizationally reshaped sphere of life. Escaping this alienation to some extent is the goal of a variety of nature-oriented leisure activities. This begins with gardening, continues with the joy of hiking, and reaches its most pronounced expression in the observation and engagement with the life processes as well as the forms and colors of nature.

Microscopist('s) interests

Detailed observation of nature is usually only possible with optical aids, in keeping with the human desire to make life easier through cultural and civilizational developments and to artificially expand the capabilities of the human senses. Since the seventeenth century, the microscope has been a tool for people to observe objects too small for the naked eye. Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), one of the great pioneers of microscopy, was a trained cloth merchant, later a civil servant in Delft, and wealthy enough to pursue his hobbies on a large scale: lens grinding, microscope construction, and nature observation and research.

The microscope is a frequently used tool in the hands of biologists, mineralogists, and in the medical field. But there is also a circle of nature lovers who devote their leisure time to this marvel of optics and precision mechanics, observing microorganisms, delighting in their shapes and colors, and exploring their lifestyles.

The interests of microscopists vary widely. For some, for example, a fascination with microscopic technology is the driving force behind their hobby, sometimes coupled with a passion for collecting; for others, the microscope opens a window to the microscopic world of life in drops of water, which also fascinated van Leeuwenhoek.

My hobby microscopy

My early introduction to the world of microorganisms was provided by a television series by the Swiss naturalist and television presenter Hans A. Traber (also employee of the microscope manufacturer Wild Heerbrugg, Switzerland), who traveled to moors and little lakes with an OB van and microscopic laboratory to amazed television audiences. His shows inspired me to buy my first microscope at the age of 14 using my savings.

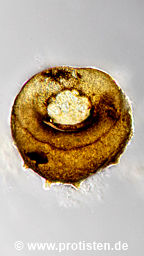

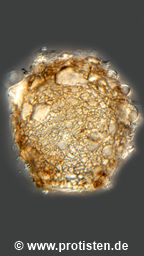

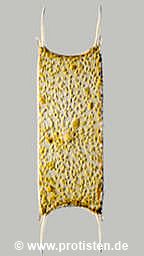

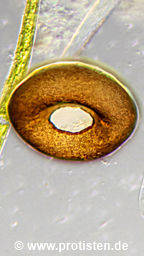

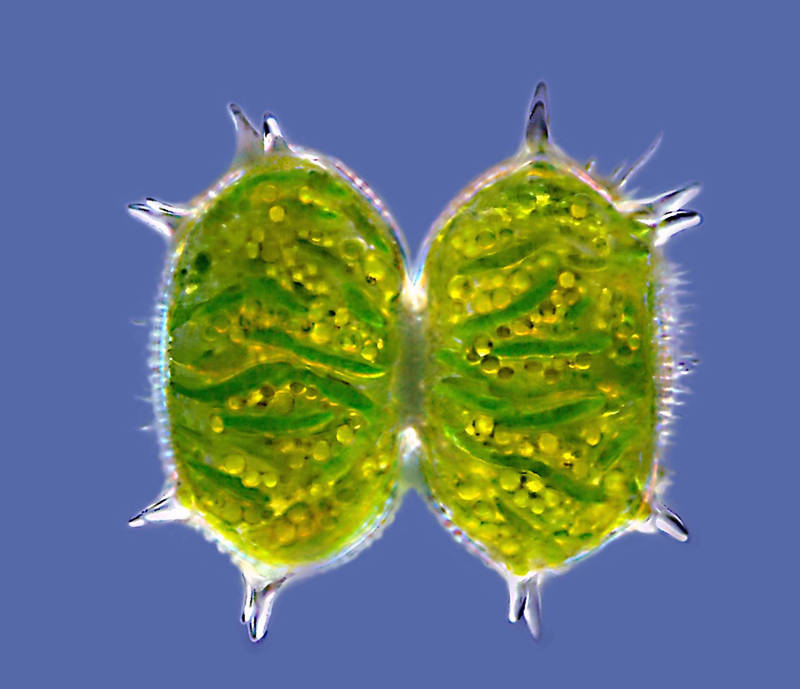

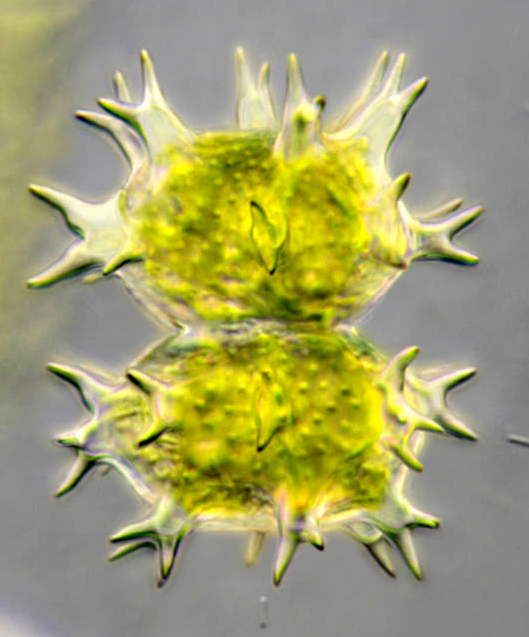

The example image below shows the desmid Xanthidium antilopaeum.

My general interest in biology and technology contributed to this, so that even as a high school student, I actively used microscopes and subscribed to and regularly read THE German magazine for micro-enthusiasts, MIKROKOSMOS. With its broad spectrum of topics, MIKROKOSMOS introduced me to the complex world of microorganisms, as well as to the cellular structures of animal and plant tissues and the fascinating world of colors of crystals in polarized light. Furthermore, it provided me with a constantly expanding textbook on microscopic techniques.

Further micro-objects

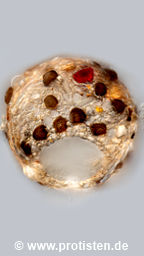

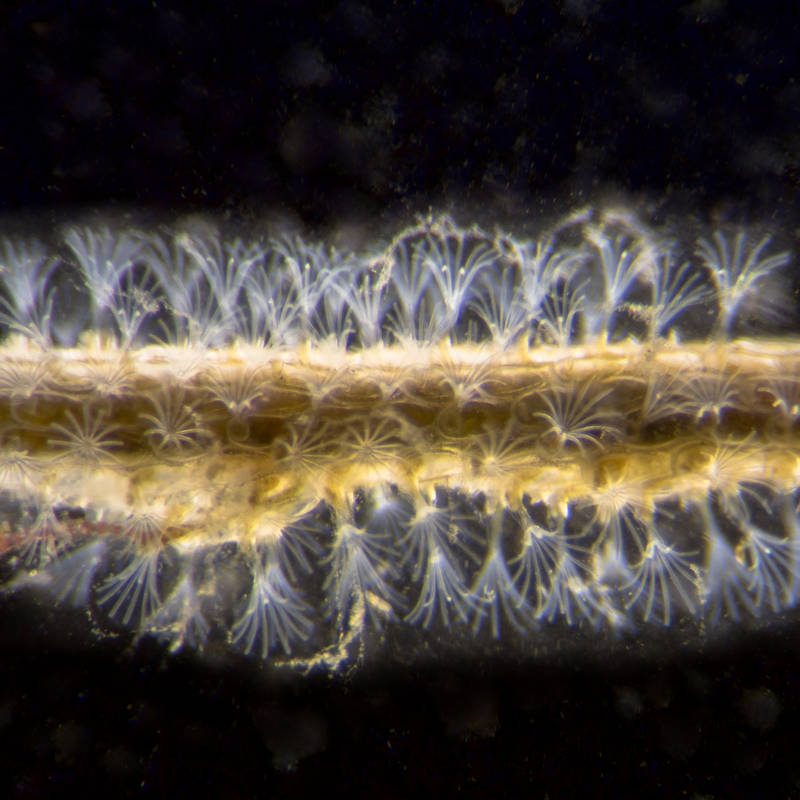

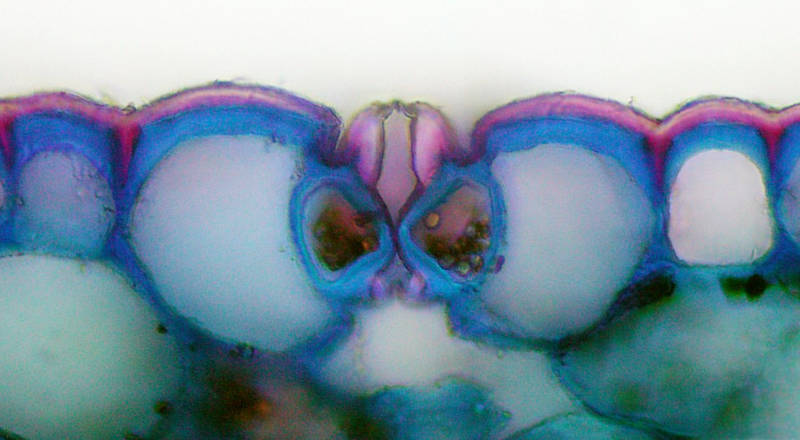

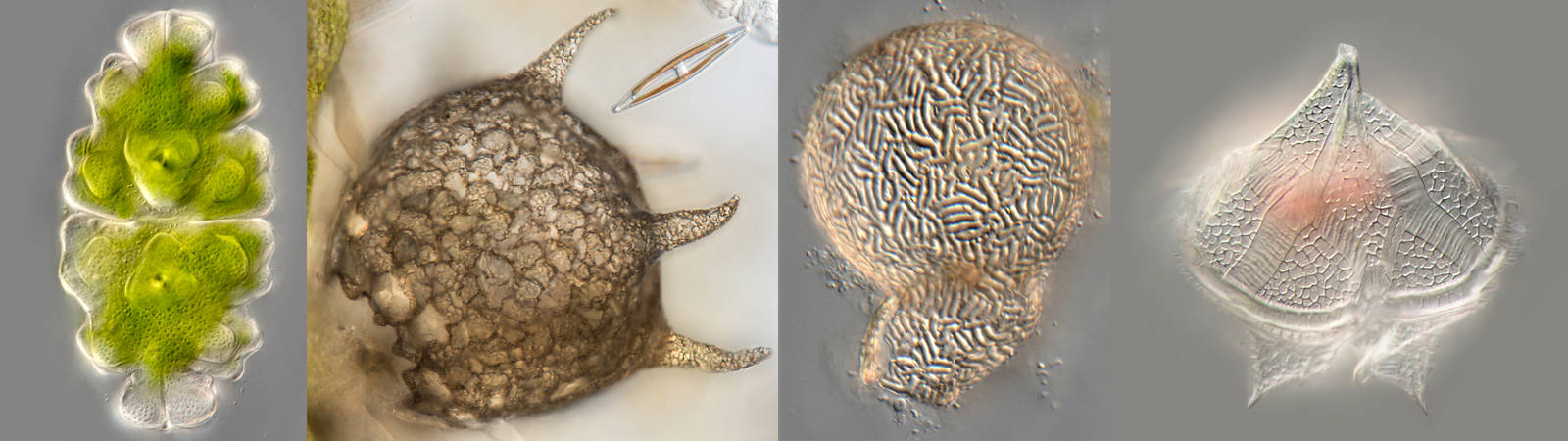

Exciting insights into the fine structure of animal and plant tissues are provided by section preparation using a razor blade or a microscopic cutting device, the microtome. To interpret and distinguish tissue structures, the sections are treated with special dyes. The left image below shows a razor blade section through a Clivia leaf.

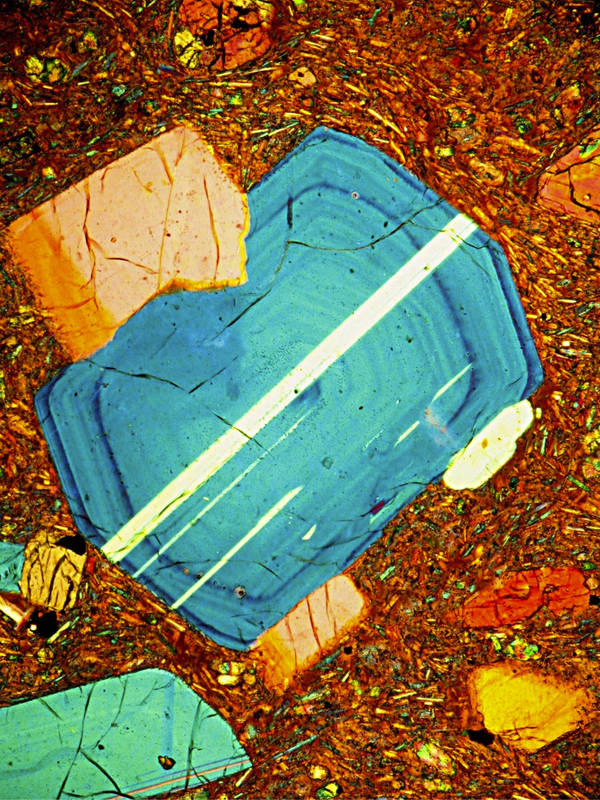

Another aesthetically pleasing world of color can be experienced by observing thin crystals grown on a microscope slide in polarized light. Similar color spectacles arise when rocks are ground into platelets a few hundredths of a millimeter thick. The right image below shows a thin section of rock in polarized light.

My microscopic career

In the young days, I had a broad interest in microorganisms in drops of water, botanical sections, and occasionally in birefringent crystals that form in solutions evaporating under a coverslip. My first microscopic phase lasted from 1970 to 1976, then came university and ‘expanding the family tree’, and there was no time for microscopy for a while. It wasn’t until 2003 that I returned to this wonderful and diverse hobby.

Since then, my field of observation has been exclusively the microscopic world in the waterdrop. The journal MIKROKOSMOS has accompanied me during my first microscopic phase; so I resubscribed to it in 2004 and contributed articles from 2006 onwards, until the publication of this valuable journal for microscopists was unfortunately discontinued by the publisher Elsevier at the end of 2014. All of the above-mentioned articles are available as PDFs in German and can be downloaded from www.protisten.de/old-content/german, which can be found in the left-hand menu bar under “Artikel”. Some have already been translated into English and can be found in the current left-hand menu bar under “Articles”.

Since 2009, however, this website protisten.de has also existed, whose goal is to make my microscopic observations publicly visible.

Since 2023, Protisten.de has been an official source for the Smithsonian Institution’s Encyclopedia of Life. I am also delighted to contribute microphotographs to Prof. Dr. Michael Guiry’s algological database Algaebase.

My natural history interests are not limited to microorganisms; I often spend time outdoors with my partner. Our animal, plant, and fungal photos can be found in our iNaturalist collection.

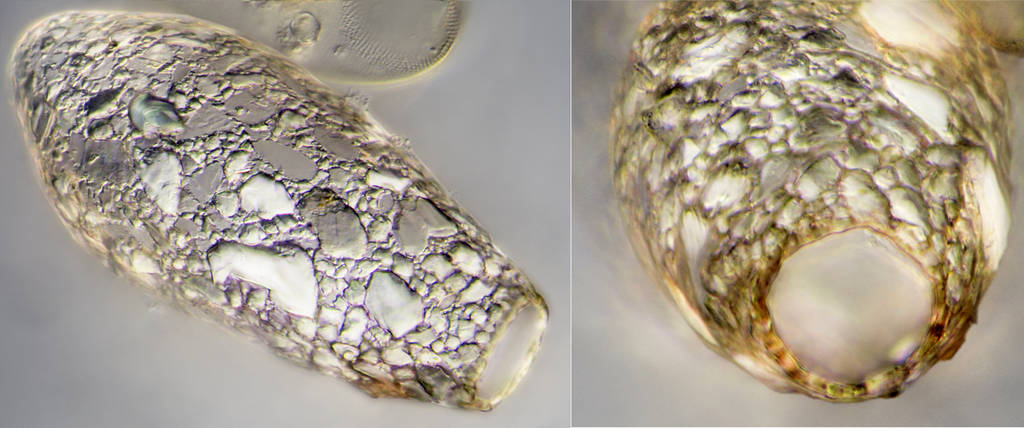

Increasing the depth of field in the microphoto by connecting image planes

All living things have a three-dimensional structure. In the macroscopic world, our brain is trained to perceive the shape of objects with the help of our two eyes. In the microscopic world, the eyes are limited by the laws of optics when it comes to scanning and capturing the entirety of the observed objects.

Hard limitations of depth of field in microscopy

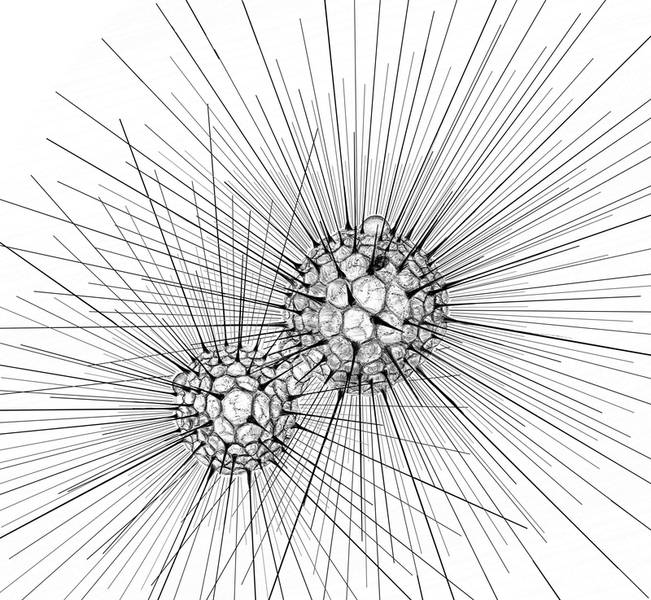

The larger the aperture (resolution) of a lens, the shallower the depth of field in its image! A photographic representation of a microorganism consisting of only a single depth of field layer is often no longer satisfactory at apertures above 0.5, because too few areas can be sharply imaged. This problem does not affect the scientific illustrators. They can create sketches or photographs of different planes of focus and reproduce a more complete image of the object in their drawing than a single photograph can.

Opportunities to overcome limitations

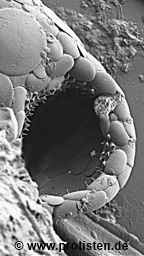

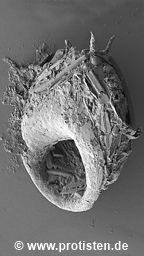

I initially practiced microscopic drawing and, over the years, developed the desire to combine photography and drawing to get closer to my ideal: the photographic capture of microorganisms without the optical limitations of a lack of depth of field. After experimenting with so-called stacking programs, which can produce excellent results in macro photography (e.g., for full-frame insect portraits), I moved on to “digital drawing.” By this I mean the method of manually combining important, sharply depicted zones from different focus planes (= different shots) into one image using layer-oriented image editing programs such as Adobe Photoshop, Corel Photopaint or GIMP. The results are multi-layer images (DOF images).

My way: manual image stacking

In a figurative sense, the pen on the digitizing tablet or the mouse is my drawing device. I use it to define the boundary lines of the important parts of the image layers from all the different focal planes, which are then interpreted as cutting lines by the image processing program.

This manual method avoids artifacts that could occur with stacking programs (e.g., incorrect highlighting or connecting edges and sharpness zones relative to the object). Just as with drawing, I can control at any area in the image and define independently of the sharpness distribution which zones of the tomographic image are important and should be transferred to the resulting image.

© Wolfgang Bettighofer,

images under Creative Commons License V 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA).

For permission to use of (high resolution) images please contact postmaster@protisten.de.

New items

discoides

gibba

cassis

elongata

oblonga

bathystoma

capreolata

var. masurica

globulosa

truncata

parva

globularis

fimbriata

chinensis

wailesii

concinnus

filifera

lineare

urceolata

enchelys

oblonga

artocrea

crenulata

spec.

brevicolla

placentula

var. euglypta

bryophila

spiralis

galeata

mitrata

gibbosa

didelta

immanata

acuminata

granulata

mucosa

var. laevicincta

rectum

bacillifera

brevicaulis

nasutum

striolatum

teliferum

pseudopyramidatum

New items

discoides

gibba

cassis

elongata

oblonga

bathystoma

capreolata

var. masurica

globulosa

truncata

parva

globularis

fimbriata

chinensis

wailesii

concinnus

filifera

lineare

urceolata

enchelys

oblonga

artocrea

crenulata

spec.

brevicolla

placentula

var. euglypta

bryophila

spiralis

galeata

mitrata

gibbosa

didelta

immanata

acuminata

granulata

mucosa

var. laevicincta

rectum

bacillifera

brevicaulis

nasutum

striolatum

teliferum

pseudopyramidatum